Artist-in-Residence: Interview with Bassem Saad

Artist-in-Residence: Interview with Bassem Saad

Bassem Saad is an artist and writer born on September 11th and trained in architecture. His work explores objects and operations that distribute violence, pleasure, welfare, and waste. Through video, sculpture, and writing, he investigates and records strategies for maneuvering within and beyond governance systems. Bassem is part of transmediale’s current artist-in-residence programme, developing a new work – Congress of Idling Persons. The work features five interlocutors that play themselves amidst broader transhistorical narratives. In the aftershocks of recent world-historical events, the film aims to map out a cartography of protest, crisis, humanitarian and mutual aid, migrant labour, and Palestinian outsider status. Congress of Idling Persons is commissioned by transmediale with the support of the Martin Roth-Initiative and will debut in full length at transmediale 2021–22 exhibition.

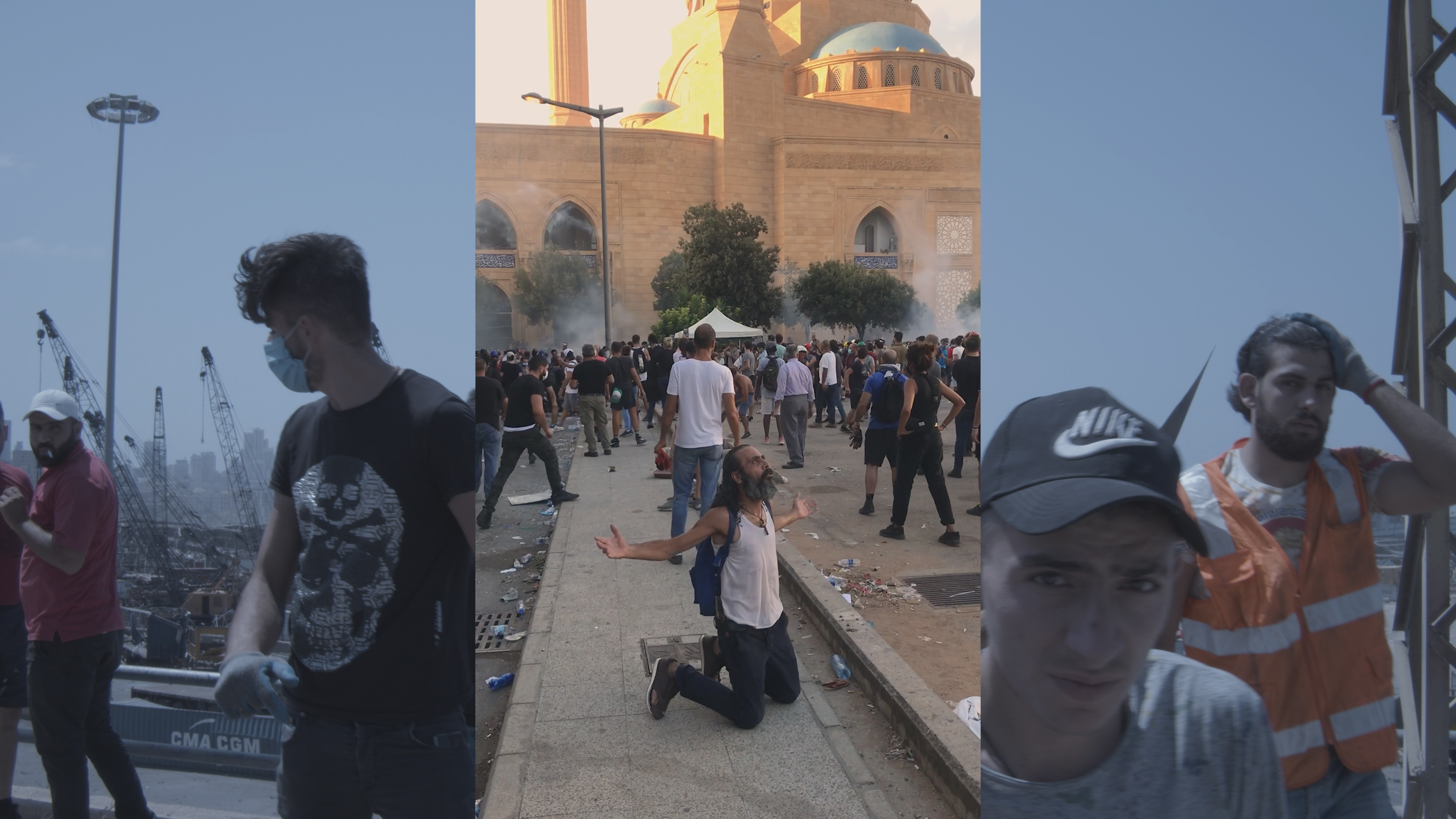

TM: Part documentary, part fiction, Congress of Idling Persons explores the aftermath of some of the most visible socio-political unrest of the past few years, including the latest Arab Spring, the Black Lives Matter protests during COVID-19 and the Beirut port explosion. Can you tell us how you connect these movements and events, and the significance of them as starting points for this film?

BS: All of the contemporary events in the film are included by virtue of my having experienced them first-hand. My entry point into each event is diaristic and almost auto-ethnographic. Some discourse recurs across different events, and they become leitmotifs, such as the figure of the outside agitator. But generally, my aim is not to draw any great conclusions about their commonalities.

TM: Can you speak about your collaborators in the film; what roles they play and how they connect to and explore larger fictions within the film?

BS: All of the performers in the film are Beirut-based individuals whose company I have kept while navigating spaces of political work. Sandy Chamoun and Rayyan Abdel Khalek are both musical artists and we have participated together closely in the October uprising. Since then, we have spent countless days in quarantine recollecting and dissecting every aspect of that period, the social actors, identity groups, police repression, crowd control, occupation and novel use of public space, mediatization by official channels and social media, competing rhetoric, and informal exchanges that collided at this historical juncture. It made sense to cast Sandy and Rayyan in a loose huit clos situation, where they are engaging each other after the commotion has somewhat died down and they’re surrounded by stillness. Islam Khatib is a Palestinian writer, who in the film is (ostensibly) seated at her desk while being interviewed, not unlike the interviews carried out historically with the writers affiliated with revolutionary movements. Mekdes Yilma is one of the co-founders of Egna Legna, a feminist migrant worker-run collective whose most recent activities include forming a robust mutual aid network in and around Beirut.

My intention in bringing all of these actors together was to form a chorus of oral counter-histories, but even that is grossly reductive. The work is not too far off from the protest anti-documentary format. The performers have no party line; they are sometimes as inconstruable as a riot.

TM: What can you tell us about your methodology of working together - how did that process shape the development of your film?

BS: Early on, I decided that my priority in allocating budget would be towards compensating the participants of the film, who I consider to be my interlocutors in producing the discourse of the work. I had multiple script development sessions with each of the performers before filming. Some felt more comfortable writing their own parts, others left it to improvise in front of the camera. So while the work is still a film-essay of sorts, it’s one that I had to (gladly) relinquish a lot of control over.

TM: How does Science Fiction influence your work? What socio-political agency does fiction employ within your practice?

BS: I’m interested in an expanded conception of science fiction, both within and beyond genre limitations. I mean to say that I’m just as interested in science and climate fictions that don’t alternate spatio-temporalities or don’t take as their subject any novel technological invention or intelligent non-human lifeforms. Some geographic contexts, like a third-world slum or refugee camp, feature no visible plant-life and no advanced algorithmic governance; they are instead awash in the brute gargle of organized abandonment, from tear gas to waterborne toxins and exposed electric circuitry. To think of political agency outside of nonfiction in those contexts and elsewhere is already science fiction, because technics and infrastructures of governmentality are always present. In this sense, I’m not intentionally creating a science-fictional work in Congress of Idling Persons, but of course it could be interpreted as such.

TM: Your work often explores resilience and conditions of labour. In this new work, you explore how migrant domestic workers are excluded from Lebanese Labour Law and instead governed by the kafala system, which ties the legal residency of the worker to the contractual relationship with the employer. Can you tell us about this system and the campaigning for its abolishment?

BS: The Kafala (sponsorship) system can be traced back to the 80s or 90s, roughly to the pronounced end of the Lebanese civil wars. Since then, up until the economic collapse in the past year, even lower-middle class households could afford to have a live-in domestic worker, because of the low wages sanctioned by the system and the difference in currency value between Lebanon and the home countries of the workers, such as Ethiopia, Philippines, Kenya, Bangladesh, and Nepal, among others. The system binds the legality of the worker’s stay in the country to her employer, who may confiscate her passport, subject her to confinement, and inflict abuse. The Kafala system is the prime local manifestation of the intersection between racial capitalism and reproductive labour.

There is a long history of activism against the Sponsorship system, by both migrant workers and Lebanese citizens. Of the latter category, most prominent is the Anti-Racism Movement, which runs the Migrant Community Center and has been active for more than ten years. Non-Lebanese citizens are not allowed to form a workers’ union, which severely attenuates the bargaining power and political agency of migrant workers in their struggle against the system; the founding congress of the Domestic Workers’ Union of Lebanon was not granted approval by the Ministry of Labour. This year, after mass lay-offs of domestic workers began taking place in the fall-out of the economic collapse, Egna Legna became more public in their activities and rose to prominence. They identify themselves as a feminist collective, and ironically, are registered as a non-governmental organization in Canada because it is also illegal for them to register as a Lebanese NGO.

TM: Jackie Wang has often critiqued how the confluence of political and antisocial tendencies in riots and rebellions are neither recognised nor embraced. Rioters are not seen as proper victims or legitimate political actors, and hence, their grievances are not acknowledged. How are you exploring the tensions between riots and socio-political demands in this work, and how do you see this in the context of Lebanon?

BS: Wang has indeed written extensively about how anti-police riots in Black communities in the United States and the United Kingdom are often either dismissed or misconstrued by white leftists. When they are not characterized as confused outbursts, riots are either exculpated of their anti-social agents or made out to be coherent and reasonable, all in the name of asserting their innocence. This sits in a centuries-long lineage of white leftists inserting the wedge of “false consciousness” between the proletariat and the lumpenproletariat – sometimes referring to racialized surplus population – spanning back to Marx himself. I’m interested in emerging scholarship around contemporary riots because we are starting to excavate this form of assembly, in a time of mass incarceration, deindustrialization, and predatory policing in the West. Joshua Clover’s work locates contemporary rioting by racialized populations in the West on a riot-strike-riot historical continuum/boomerang, after the waning of the labour movement and workers’ ability to strike since the 80s onwards.

In the Arab world, the riot has emerged since the start of the Arab spring as the paradigm for the spark-event that sets off an uprising. I write this in the week of the 10-year anniversary of the start of the Arab spring, when the Tunisian street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi self-immolated, opening the floodgates—I still tear up sometimes when I see a photo of Bouazizi. The Iranian scholar Asef Bayat has written about the subjectivity of the “urban subaltern” in Arab cities and elsewhere: nationals and migrants, who, like Bouazizi, rely on informal labour for subsistence, and are largely underemployed or unemployed. These individuals cannot strike or bargain by withdrawing their labour. Bayat refers to the riots and mobilization carried out by these populations as “non-movements;” this is perhaps not the most auspicious coinage.

The October uprising in Lebanon began similarly, when a group of young people from the southern suburbs flocked spontaneously to downtown Beirut and set it alight on October 17th, 2019, after a tax on WhatsApp was proposed. Later on, different interest groups and political blocs emerged and began articulating socio-economic demands, which ran the spectrum from ultra-leftist to fully complicit with the hegemonic sectarian-clientelist system. Yet that initial rioting crowd is not easily tracked down, not easily pre-empted, foreseen, or made legible.

TM: Since 2015 there have been significant protests and riots among different groups against the state in Lebanon. The recognition of common experiences of oppression has resulted in acts of solidarity across many of these groups. Can you speak about how this is explored in your film?

BS: As with any popular uprising, the October uprising brought together a multitude of divergent identities and interest groups, who expressed solidarity, but were also largely agonistic and at great odds with one another. In the film, Islam Kathib speaks brilliantly about the equivalences between providing aid and extending solidarity, which are both gestures fraught with forced circumscription, false equivalence, and replication of hierarchy. She draws a provocative analogy between extending solidarity and giving humanitarian aid, and speaks around the limits of both.

TM: In the Congress of Idling Persons, you look at historical and contemporary moments in which different social groups have conceptualised and practiced democratic biopolitics. The notion of biopolitics has been associated with the relationships between health, politics, racism, and social antagonism. Can you speak about the possibilities of democratic biopolitics and how they emerge as part of contemporary radical strategies of refusal and protest?

BS: The groups of people I’m describing above, from racialized populations in de-industrialized towns and metropoles in the West, to the urban subalterns in the Global South, often do not have “workplace demands” but grievances related directly to their life and death, because they are always faced either with decrepit infrastructures and total abandonment, or the boot of police repression. Perhaps I’m stretching the term democratic biopolitics to the point where it is too capacious to be useful, but what I’m referring to are forms of organizing that concern themselves directly with their subject’s welfare outside of the workplace, from tenants’ unions to mutual aid groups. In the film, Mekdes speaks about how Egna Legna attempt to disseminate some form of political discourse or call to action through their distribution of aid.

TM: You’ve often spoken about how neoliberal governmental policy and racial capitalism aim to snuff out political will and ambition for anything beyond mere physical safety and fulfillment of basic needs. Yet, within your work, there is a sense of hopefulness in relationships and kinship. Can you speak about the interconnections between refusal and hope in your work?

BS: As Jackie Wang notes, a pure politics of refusal is not viable. Abolition (of the police, the prison-industrial complex, the Kafala system) is total refusal, but it is not “for nothing, and against everything.” There are networks being built in the long haul, in times of relative stillness. Hope is a treacherous affect, and it is one that is easily co-opted in the rhetoric of neoliberal development after this or that crisis. That is a disclaimer, but it is not a call to reject the ebullience of affect and desire in moments of revolutionary fervour. But we need our buffers against disillusionment, and I think these can only be found in the relations and community that are maintained in these other moments, when the world happens to not be convulsing in revolt.